Mentuhotep II, a forgotten yet pivotal figure in Ancient Egyptian history. Despite his significance, few are familiar with the face of this 11th dynasty ruler. But, by the end of this article, you will understand why his legacy is hidden from the public. Mentuhotep II was the son of King Intef III and Queen Iah, who may have also been his sister. This familial connection is supported by the Stele of Henenu, a trusted official under both Intef II and Mentuhotep II.

The pharaoh had several wives, including Tem who was likely his chief wife and bore the title of King’s wife and King’s mother. Neferu II, another of Mentuhotep II’s wives, was called King’s wife and eldest king daughter of his body. Kawit was a secondary wife and priestess of the goddess Hathor, and Sadeh, Ashayet, Henhenet, and Kemsit were also secondary wives and priestesses of Hathor. A five-year-old girl, Mwyt, was buried with Mentuhotep II’s secondary wives and is believed to be one of his daughters.

These women were all buried with or near Mentuhotep II in his mortuary temple, with the exception of Neferu II who was buried in the tomb TT319 of Deir el-Bahri. The discovery of their tombs and sarcophagi have provided valuable insights into the personal life and relationships of Mentuhotep II and his wives.

Reign

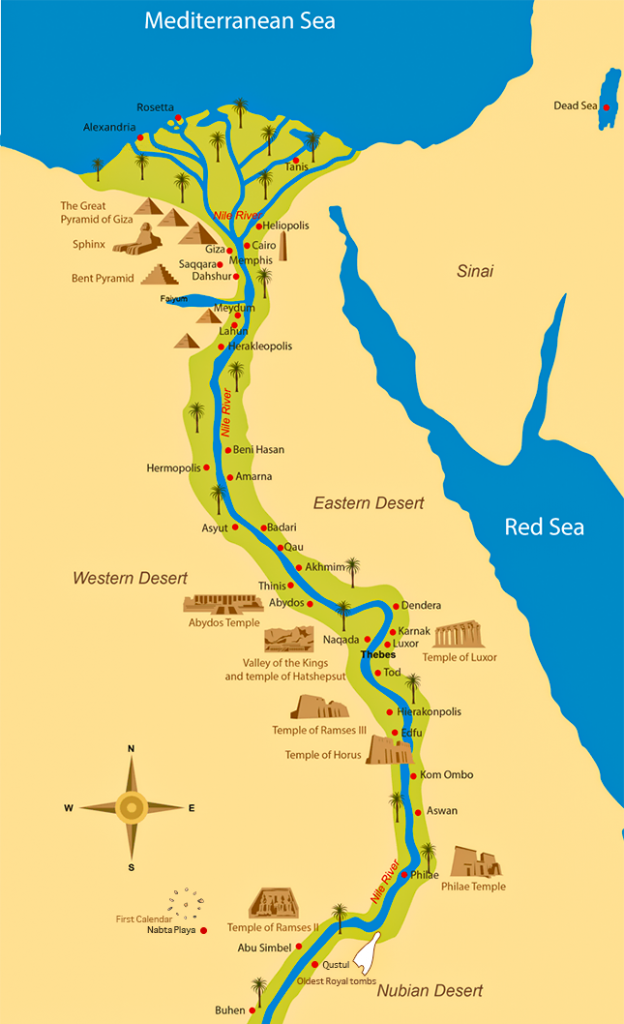

With the ascension to the Theban throne, Mentuhotep II became the first ruler of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt and marked a new era of power and prosperity. Inheriting a vast land that extended from the first cataract in the south to Abydos and Tjebu in the north, Mentuhotep’s first fourteen years were marked by peace and tranquility in the Theban region. No surviving traces of conflict from that period could be firmly dated. In fact, the scarcity of testimonies from the early part of Mentuhotep’s reign might suggest that he was young when he took the throne, which aligns with his impressive 51-year reign, recorded in the Turin Canon. The rise of Mentuhotep II marked the beginning of a new era in the history of Egypt, one that would come to define the Middle Kingdom.

Reunification of Egypt

The reign of Mentuhotep II was marked by a defining moment in the 14th year when an uprising broke out in the north of Egypt. The conflict was tied to the ongoing struggle between Mentuhotep based in Thebes and the rival 10th Dynasty based at Herakleopolis, who sought to conquer the Thinite region and desecrate the sacred royal necropolis of Abydos. To defend his kingdom, Mentuhotep dispatched his armies and was successful in quelling the uprising. The famous tomb of the warriors at Deir el-Bahari, discovered in the 1920s, holds the bodies of 60 soldiers who gave their lives in battle and bore the markings of Mentuhotep’s cartouche. The weakened state of Lower-Egypt, possibly due to the death of Merikare during the conflict, provided Mentuhotep the opportunity to reunite all of Egypt, a process that may have taken time and was completed shortly before the 39th year of his reign. The reunification of Egypt under Mentuhotep II solidified his divine status among his subjects, a reverence that persisted for centuries as evidenced by the stelae erected by later Pharaohs Senusret III and Amenemhat III commemorating the opening of the mouth ceremonies performed on Mentuhotep’s statues.

Military activities outside Egypt

King Mentuhotep II was a man of action. Under his command, his army set out to reclaim Nubia, a land that had gained its independence during a time of great turmoil in Egypt known as the First Intermediate Period. This marked the first time the term “Kush” appeared in Egyptian records to describe Nubia.

To ensure swift and decisive military action, King Mentuhotep posted a garrison on the island fortress of Elephantine. This strategic move allowed his troops to be deployed rapidly to the south. The king’s army was not content with only reestablishing control over Nubia. There is also evidence that they launched military campaigns against the neighboring land of Canaan.

The King’s influence and reach extended far beyond Egypt’s borders. At Gabal El Uweinat, a region near the modern borders of Libya, Sudan, and Chad, an inscription was found that bears the king’s name. This inscription attests to the fact that King Mentuhotep had trade contacts with this far-off land. It is a testament to his leadership and the power of his empire.

Mentuhotep II was a visionary leader who understood the importance of expanding Egypt’s sphere of influence. His military campaigns and strategic garrisons helped to secure Egypt’s place as a dominant power in the ancient world

Reorganization of the government

King Mentuhotep II took decisive action to reorganize the administration of Ancient Egypt, placing a vizier at the head of government operations. He appointed two prominent viziers during his reign, Bebi and Dagi, and Kheti served as his treasurer and played a key role in organizing the king’s sed festival. Other important officials included Meketre as treasurer and Meru as overseer of sealers, and Intef served as the king’s general.

During the First Intermediate Period, the nomarchs held significant power in Egypt, with their office having become hereditary during the 6th Dynasty. However, after Mentuhotep successfully unified Egypt, he implemented a strong policy of centralization, creating the posts of Governor of Upper Egypt and Governor of Lower Egypt with the authority to oversee the local nomarchs.

Mentuhotep further solidified his royal authority by relying on a mobile force of royal court officials to monitor the actions of the nomarchs. This helped him to reassert control over the powerful nomarchs who had previously held sway during the First Intermediate Period. He also initiated an extensive program of self-deification, emphasizing the divine nature of the ruler and further consolidating his power.

Monuments

The reign of Mentuhotep II marked a significant period in Ancient Egyptian history, as he commanded the construction of many temples, though only a few have survived to this day. The funerary chapel in Abydos, discovered in 2014, is one of the well-preserved examples of Mentuhotep’s architectural achievements. Most of the other temple remains are located in Upper Egypt, in cities such as Abydos, Aswan, Tod, Armant, Gebelein, Elkab, Karnak, and Denderah. This building tradition was continued from his grandfather Intef II, who began royal building activities in the provincial temples of Upper Egypt during the Middle Kingdom.

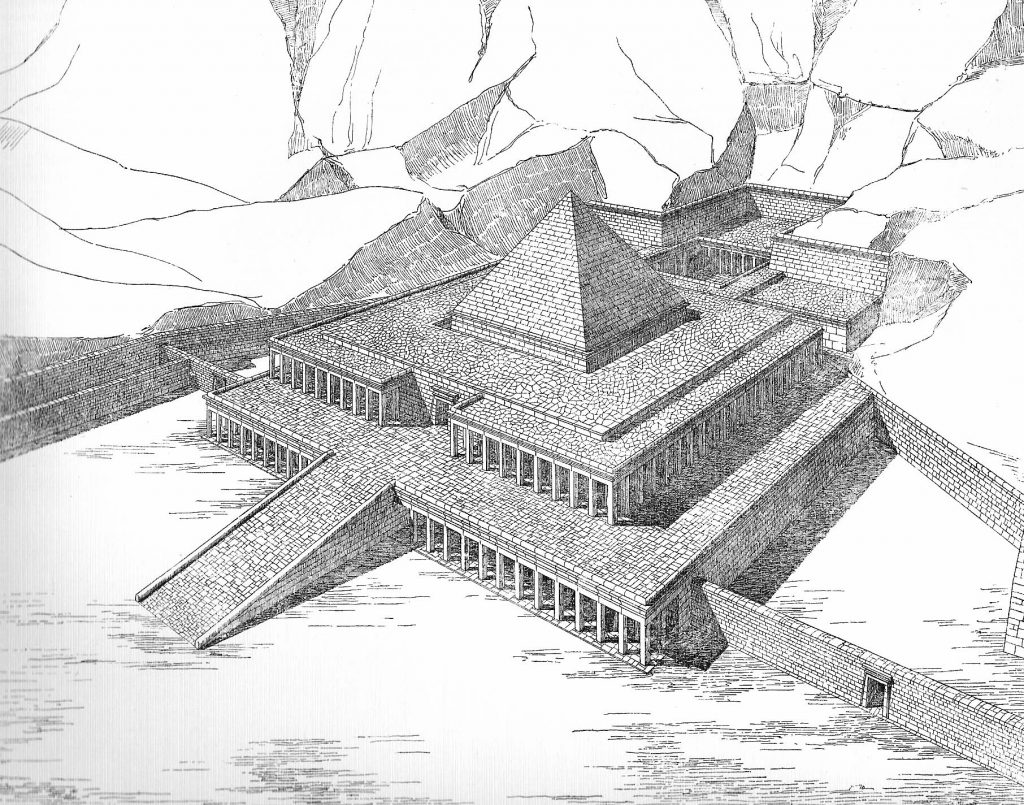

Mentuhotep II’s most impressive building project was his large mortuary temple, located in the cliff at Deir el-Bahri on the west bank of Thebes. This temple was a major source of inspiration for later temples such as those of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. However, the most remarkable innovations of this temple are religious in nature. For the first time, the king was not just the recipient of offerings but rather performed ceremonies for the deities, in this case, Amun-Ra. The temple also identified the king with Osiris, a belief evident in the funerary statuary of many later pharaohs.

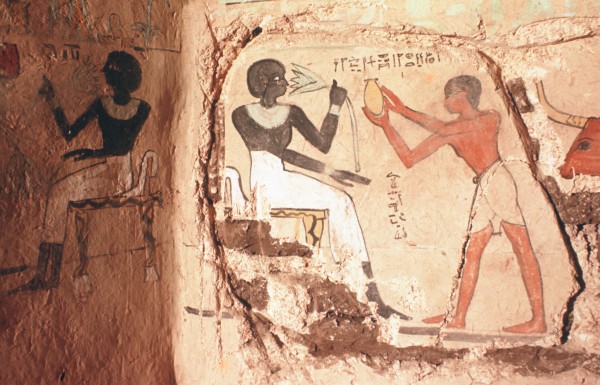

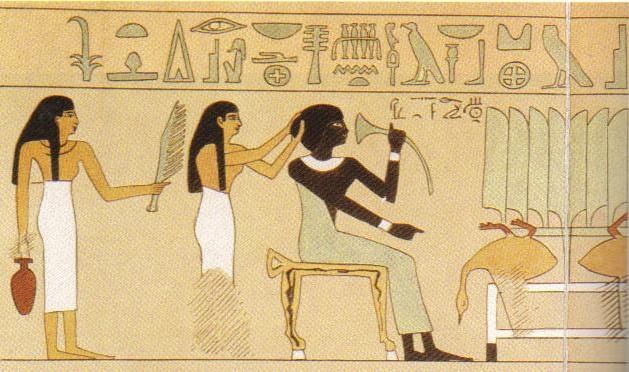

The decoration of the temple was created by local Theban artists, which is evident from the dominant artistic style, characterized by large lips and eyes and thin bodies. At the opposite end, the refined chapels of Mentuhotep’s wives were the work of Memphite craftsmen heavily influenced by Old Kingdom standards. This fragmentation of artistic styles is a direct consequence of the political fragmentation of the country, which is observed throughout the First Intermediate Period.

The mortuary complex of Mentuhotep II comprised two temples, the high temple of Deir el-Bahri and a valley temple closer to the Nile on cultivated lands. The valley temple was linked to the high temple by a 1.2 km long and 46 m wide uncovered causeway. The courtyard in front of the Deir el-Bahri temple was adorned by a rectangular flower bed and fifty-five sycamore trees planted in small pits and six tamarisk and two sycamore trees planted in deep pits filled with soil. This temple garden, located over 1 km from the Nile into the arid desert, required constant maintenance and an elaborate irrigation system.

Left and right of the processional walkway were at least 22 seated statues of Mentuhotep II, wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt on the south side and the Red Crown of Lower Egypt on the north side. These statues were probably added to the temple for the celebration of Mentuhotep’s Sed festival during his 39th year on the throne. Some headless sandstone statues remain on site today, while another was discovered during Herbert Winlock’s excavations in 1921 and is now on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The temple in ancient Egypt of Mentuhotep II was a complex structure dedicated to the worship of the sun god Ra and the Theban god of war Monthu, as well as the deified king and the god Amun-Ra. The front part of the temple, located to the west of the causeway, was dedicated to Monthu-Ra and consisted of a ramp leading to the upper terrace, two porticos with a double row of rectangular pillars, and a massive core building. The front part of the temple was designed to resemble a saff tomb, the traditional burial of Mentuhotep II’s 11th-Dynasty predecessors.

The rear part of the temple, located behind the core edifice, was dedicated to Amun-Ra and was cut directly into the cliff. This part of the temple consisted of an open courtyard, a hypostyle hall with 82 octagonal columns, a sanctuary dedicated to Mentuhotep and Amun-Ra, and a chapel for a statue of the king. The open courtyard was surrounded by walls and columns and led to a dromos that descended to the royal tomb.

The royal tomb was located in a large underground chamber 45 meters below the open courtyard and was lined with red granite. The tomb contained an alabaster chapel in the form of an Upper-Egyptian Per-wer sanctuary and was once closed by a double door that is now missing. Although much of the grave goods have been lost due to tomb plundering, a few items such as a scepter, arrows, and models of ships, granaries, and bakeries have been recovered.

These remnants of ancient Egyptian history serve as a reminder of the religious and architectural significance of the Mentuhotep II temple and the profound religious changes in the ideology of kingship that took place during this time period. The temple was a testament to the power of the pharaohs and their close relationship with the gods, as well as their dependence on the gods’ goodwill for their immortality.

Nubian origin theory

During the Middle Kingdom, the role of Nubian bowmen was critical for the development of the Egyptian state. In fact, if the supposition that its founder, Mentuhotep II, was of possible Nubian origin, then it is even less surprising that the tomb models of Nubian archer-soldiers were so popular at this time. Some scholars have also suggested that he was Nubian because the iconography depicted him with pronounced Nubian facial features. This is likely why he remains relatively unknown in mainstream media, despite his significant impact on Ancient Egyptian history. The most revered pharaohs were those who achieved what was deemed impossible at the time – reunifying Upper and Lower Egypt. Mentuhotep II is one of them.

This article is part of the restoration project, which aims to combat the longstanding distortion of African history through visuals or representation. For too long, ancient African figures who accomplished great things have been misrepresented as white or white-passing, while the contributions of all groups of people have been erased or minimized. This systematic falsification of history has had a damaging effect on the self-esteem and opportunities of African people, and has contributed to the oppression they experience in their daily lives.

I am excited to present a facial reconstruction of Pharaoh Mentuhotep II, created with attention to detail in depicting his facial features and a skin tone commonly found in the population of Upper Kemet and Nubia. It offers a glimpse into the appearance of this remarkable ruler. I hope you will appreciate the care taken in its creation, and note that improvements may be made as my skills develop.

If you would like to support this initiative, please consider making a donation or spreading the word about the ‘Restoration Project’ to your network. Together, we can work towards a future where all groups of people are accurately and fairly represented in the historical narrative. Thank you for visiting our website and for supporting this important cause.

Or become an architect, join the builders on Patreon

References:

- Dictionary of Ancient Egypt – Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. - Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia – Richard A. Lobban Jr.

- Callender, Gae (2003). “The Middle Kingdom Renaissance (c. 2055–1650 BC)”. In Shaw, Ian (ed.).

- The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Egypt –Morris L. Bierbrier

- Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire – Drusilla Dunjee Houston